BY K CHANDRU PUBLISHED IN THE HINDU

BY K CHANDRU PUBLISHED IN THE HINDU

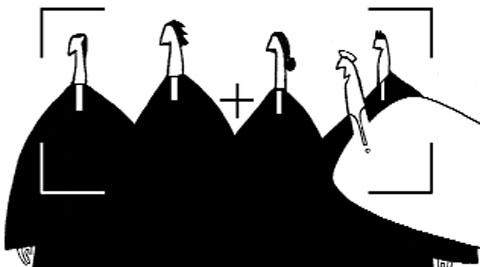

Senior advocate Fali S. Nariman appearing in cases before the Supreme Court where his son is a judge has revived an old debate regarding the appropriateness of such appearances

In 1967, when U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed the son of U.S. Supreme Court Judge Tom C. Clark as the Attorney General, Clark promptly resigned from his post. This was because an Attorney General will have to make frequent appearance in the court in which his father will be one of the judges adorning the bench and in that Supreme Court all the nine judges sit together. But in India that has not been the case. Right now the matter regarding the appropriateness of a lawyer appearing in a court in which his near relative is a judge has gained significance in the context of Fali S. Nariman, a leading senior advocate of the Supreme Court, continuing to appear in cases before the Supreme Court in which his son Rohinton F. Nariman has become a Judge since July 2014. While some criticism was aired regarding this in public, Mr. Nariman dismissed complaints maintaining that there is no legal bar for such appearance and said that everyone is equal before the law.

What rules say

Until 1961, in India, there were instances in which lawyers appeared in the same court over which their relatives were presiding. But after the Advocates Act, 1961 empowered the Bar Council of India to frame rules on the matter, such incidences have become rare. Under Rule 6 of the norms established by the Bar Council, no lawyer can practise in a court where any of his relatives functions as a judge. The list of such relatives included his/her father, grandfather, son, grandson, uncle, brother, nephew, stepbrother, husband, wife, daughter, sister, aunt, niece, father-in-law, brother-in-law or sister-in-law. However, there have been controversies as to whether the term ‘court’ mentioned in this Rule refers only to the court of that particular judge or the entire court where the relative works.

During the early 1980s, this rule came up for interpretation before the Karnataka High Court. Pramila Nesargi, a woman advocate who got married to Nesargi, a Karnataka High Court Judge who had lost his wife at that time, appeared before the court of Justice P.P. Bopanna. She was not a senior advocate at that time and as her name did not find mention in the vakalat filed in that case, the Judge directed her to file a vakalat to represent her client. The next day when her name appeared in the cause list, the judge who heard her case refused to allow her to appear before any judge in the Karnataka High Court.

He ruled: “The Bar Council prohibits a lawyer from appearing in a Court where a close relative works as a judge. While the term ‘court’ does not specifically refer to all the courts in a particular High Court, we should be strict in respect of a wife. A wife has an intimate relationship with her husband. Many matters discussed among judges would reach her ears. When a woman who has access to confidential matters in respect of a Court is allowed to practise in the same Court as a lawyer, it can spell danger.”

” Advocates Act, 1961 empowered the Bar Council of India to frame rules so that no lawyer can practise in a court where any of his relatives functions as a judge. ”

Subsequently, the matter was raised before the Supreme Court which ordered notice to the Bar Council. But the case was not taken to its logical end and the matter became infructuous as the counsel involved became a senior advocate and the Judge concerned was superannuated. Yet the controversy over the interpretation of the rule still continues to haunt the courts. When Justice P. Balakrishna Iyer became a judge of the Madras High Court, his son advocate P. B. Krishnamoorthy shifted his practice to another State. There was also a strange practice adopted by a lawyer in the early 1970s. The said lawyer used to sign hundreds of memos of appearances in bail applications so that those matters will not go before his father-in-law judge, who was known to be strict regarding granting of bail.

When Justice V. R. Krishna Iyer became a Supreme Court judge, his son who was a lawyer as well, chose not to practise in any court in India opting for private employment. Justice V. Sivaraman Nair of the Kerala High Court had worked as a junior of Justice Krishna Iyer. But as soon as his daughter and daughter-in-law started practising in the Kerala High Court, he requested the President of India to transfer him to another State.

Justice Leila Seth, a former Chief Justice of Himachal Pradesh writing in her autobiography recalled her experience in the Patna High Court regarding the two kinds of ‘practice’ the Bar had adopted.

She wrote: “I heard people talking about ‘Uncle Practice’ and ‘Lal Jhanda’. I wondered what all this was about. I learnt that, since a son was not permitted practice in his father’s court, if you did not want the matter to be heard by that court, you briefed the son and thus stopped the matter from going before the father; you had put out a warning ’Red Flag’. This misuse of a rule that had been incorporated to prevent partisan decisions was apparently quite prevalent, and some young lawyers even managed to make a living out of it. It was also rumoured that certain judges favoured the sons of their brother judges, and so the ‘Uncle Practice’ thrived.”

In S. P. Gupta’s case (1981) dealing with the judges’ transfer issue relating to close relations taking undue advantage of a sitting judge, the following way out was suggested to avoid embarrassment: “We have to take into account the advice given by the CJI in one of the seminars that where close relations of a Judge or the Chief Justice practise in the same court and are likely to gain undue advantage, the concerned judge should himself, in obedience to the keen sense of justice which every Judge possesses opt to be transferred to some other High Court.”

In S. P. Gupta’s case (1981) dealing with the judges’ transfer issue relating to close relations taking undue advantage of a sitting judge, the following way out was suggested to avoid embarrassment: “We have to take into account the advice given by the CJI in one of the seminars that where close relations of a Judge or the Chief Justice practise in the same court and are likely to gain undue advantage, the concerned judge should himself, in obedience to the keen sense of justice which every Judge possesses opt to be transferred to some other High Court.”

In 1997, all the judges of the Supreme Court assembled under the Chairmanship of Chief Justice J. S. Verma and adopted a resolution on ‘The Values in Judicial Life’. That resolution stated that a judge should prohibit a close relative of his from appearing in his court. It also stated that no relative of his should practise law while staying in the Judge’s house. Markandeya Katju, in his judgment in Raja Khan’s case, sounded a warning on the ills of kith and kin being allowed to practise in the same court as their relatives. He said: “Some Judges have their kith and kin practising in the same court, and within a few years of starting practice the sons or relations of the Judge become multimillionaires, have huge bank balances, luxurious cars, huge houses and are enjoying a luxurious life. This is a far cry from the days when the sons and other relatives of Judges could derive no benefit from their relationship and had to struggle at the bar like any other lawyer.”

What is the way out?

When Justice R. M. Lodha took over as the Chief Justice of India, some presspersons raised a question as to whether it was not possible to prohibit relatives of a judge from practising as lawyers in the same Court. He replied that it was up to the Bar to find a solution to the problem. He also dismissed a public interest litigation filed by advocate M. L. Sharma seeking a ban on the relatives of judges practising in the same courts.

With the controversy reviving in the context of Mr. Nariman appearing in the court where his son is a judge, the Bar Council of India must be called upon to suitably amend relevant rules and uphold the faith of the common man in the judiciary.

(K. Chandru is a retired Judge of the Madras High Court.)

Correction

>>There was a reference to Justice A.S. Bopanna in the Comment page article – “Father, son and the holy Court” (Oct. 24, 2014). It should have been Justice P.P. Bopanna.