Remarks by Lord Justice Leveson: Thursday 29 November 2012

For the seventh time in less than 70 years, there is a new report, commissioned by the Government, dealing with concerns about the press. It was sparked by public revulsion about a single act – the hacking of the mobile phone of a murdered teenager. From that beginning, it has expanded to cover the culture, practices and ethics of the press and its conduct in relation to the public, the police and politicians.

This Inquiry has been the most concentrated look at the press this country has ever seen. In nearly nine months of oral hearings, 337 witnesses gave evidence in person and the statements of nearly 300 others were read into the record. I am grateful to all who have contributed. The Report will now be published on the Inquiry website which also carries the statements, exhibits and both transcripts and video coverage of the evidence.

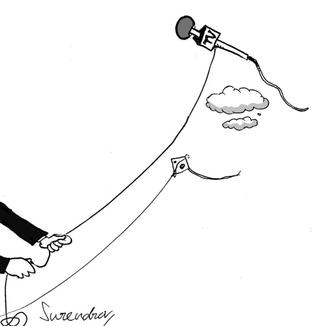

For over 40 years, as a barrister and a judge, I have watched the press in action, day after day, in the courts in which I have practised. I know how vital the press is – all of it – as guardian of the interests of the public, as a critical witness to events, as the standard bearer for those who have no-one else to speak up for them. Nothing in the evidence I have heard or read has changed that view. The press, operating freely and in the public interest, is one of the true safeguards of our democracy. As a result, it holds a privileged and powerful place in our society.

But this power and influence carries with it responsibilities to the public interest in whose name it exercises these privileges. Unfortunately, as the evidence has shown beyond doubt, on too many occasions, those responsibilities (along with the Editors’ Code which the press wrote and promoted) have simply been ignored. This has damaged the public interest, caused real hardship and, also on occasion, wreaked havoc in the lives of innocent people.

What the press do and say is no ordinary exercise of free speech. It operates very differently from blogs on the internet and other social media such as Twitter. Its impact is uniquely powerful. A free press in a democracy holds power to account. But, with a few honourable exceptions, the UK press has not performed that vital role in the case of its own power.

None of this, however, is to conclude that press freedom in Britain, hard won over 300 years ago, should be jeopardised. On the contrary, it should not. I remain firmly of the belief that the British press – I repeat, all of it, – serves the country very well for the vast majority of the time. There are truly countless examples of great journalism, great investigations and great campaigns. Not that it is necessary or appropriate for the press always to be pursuing serious stories for it to be working in the public interest. Some of its most important functions are to inform, educate and entertain and, when doing so, to be irreverent, unruly and opinionated.

But none of that means that the press is beyond challenge. I know of no organised profession, industry or trade in which the serious failings of the few are overlooked or ignored because of the good done by the many. Were it so in any other case, the press would be the very first to expose such practices.

The purpose of this Inquiry has been two fold. First, it has been to do just that – to expose precisely what has been happening. Secondly, it is to make recommendations for change. As to change, almost everyone accepts that the Press Complaints Commission has failed in the task, if indeed it ever saw itself as having such a task, of keeping the press to its responsibilities to the public generally and to the individuals unfairly damaged.

There must be change. But let me say this very clearly. Not a single witness proposed that either Government or politicians all of whom the press hold to account, should be involved in the regulation of the press. Neither would I make any such proposal.

Let me deal very briefly with the idea that this Inquiry might not have been necessary if the criminal law had simply operated more effectively. There were errors in aspects of the way the phone hacking investigation was managed in 2006 and in relation to the failure to undertake later reviews, and there are some problems that need to be fixed with the criminal and civil laws and also in relation to data protection. In particular, exemplary damages should be available for all media torts. In the end, however, law enforcement can never be the whole answer. As we have seen, that is because the law-breaking in this area is typically hidden, with the victims generally unaware of what has happened. Even if it were possible – and it is certainly not desirable – putting a policeman in every newsroom is no sort of answer.

In any event, the powers of law enforcement are significantly limited because of the privileges that the law provides to the press, including for the protection of its sources. That is specifically in order that it can perform its role in the public interest. What is needed therefore is a genuinely independent and effective system of selfregulation of standards, with obligations to the public interest. At the very start of the Inquiry and throughout I have encouraged the industry to work together to find a mechanism for independent self-regulation that would work for them and would work for the public.

Lord Hunt of Wirral and Lord Black of Brentwood stepped forward to lead the effort. They put forward the idea of a model based on contractual obligations among press organisations. On Monday afternoon of this week, with the Report being printed, I received two separate submissions from within the press telling me that most of the industry was now prepared to sign self-regulation contracts.

The first submission recognises the possibility of improvements to the model proposed so far. The second expresses confidence that the model proposed by Lord Black and Lord Hunt addresses the criticisms made at the Inquiry. Unfortunately, however, although this model is an improvement on the PCC, in my view, it does not come close to delivering, in the words of the submission itself, “regulation that is itself, genuinely, free and independent both of the industry it regulates and of political control”. Any model with editors on the main Board is simply not independent of the industry to anything approaching the degree required to warrant public confidence. It is still the industry marking its own homework. Nor is the model proposed stable or robust for the longer-term future.

The press needs to establish a new regulatory body which is truly independent of industry leaders and of Government and politicians. It must promote high standards of journalism, and protect both the public interest and the rights and liberties of individuals. It should set and enforce standards, hear individual complaints against its members and provide a fair, quick and inexpensive arbitration service to deal with civil law claims.

The Chair and the other members of the body must be independent and appointed by a fair and open process. It must comprise a majority of members who are independent of the press. It should not include any serving editor or politician. That can be readily achieved by an appointments panel which could itself include a current editor but with a substantial majority demonstrably independent of the press and of politicians. In the Report, I explain who might be involved.

Although I make some recommendations in this area, it is absolutely not my role to seek to establish a new press standards code or to decide how an independent selfregulatory, body would go about its business. As to a standards code, I recommend the involvement of an industry committee (which could involve serving editors).

That committee would advise the regulatory body and there should be a process of public consultation. In my report, I also address the need for incentives to be put in place to encourage all in the industry to sign up to this new regulatory system. Guaranteed independence, long-term stability, and genuine benefits for the industry, cannot be realised without legislation. So much misleading speculation and misinformation has been spread about the prospect of new legislation that I need to make a few things very clear. I am proposing it only for the narrow purpose of recognising a new independent self-regulatory system. It is important to be clear what this legislation would not do; it would not establish a body to regulate the press; that is for the press itself to do.

So what would this legislation achieve? Three things. It would enshrine, for the first time, a legal duty on the Government to protect the freedom of the press. Secondly, it would provide an independent process to recognise the new self-regulatory body and thereby reassure the public of its independence and efficacy. Thirdly, it would provide new and tangible benefits for the press. As members of the body, newspapers could show that they act in good faith and have sought to comply with standards based on the public interest. Decisions of the new recognised regulator could create precedents which could, in turn, help a court in civil actions. In addition, the existence of a formally recognised, free arbitration system is likely to provide powerful arguments as to costs should a claimant decide not to use that free system or, conversely, if a newspaper is not a member. In my view, the benefits of membership should be obvious to all.

This is not, and cannot reasonably or fairly be characterised as, statutory regulation of the press. I am proposing independent regulation of the press organised by the press itself with a statutory process to support press freedom, provide stability and guarantee for the public that this new body is independent and effective. I firmly believe that these recommendations for self-regulation are in the best interests of the public and the press; they have not been influenced by any political or other agenda but solely by what I believe is fair and right for everyone. What is more, given the public interest role of which the press is rightly proud, I do not think that either the victims I have heard from, or the public in general, would accept anything less.

Turning to the police, the relationship between police and public is vital to the essential requirements of policing by consent and the press have a very important part to play in its promotion. Although there has been a limit on how far it has been possible for the Inquiry to go because of the need not to prejudice any ongoing investigations, whatever Operation Elveden (concerning corrupt payments to officials) might reveal, I have not seen any evidence to suggest that corruption by the press is a widespread problem in relation to the police. However, while broadly endorsing the approach of recent reviews into police governance, I have identified a number of issues that I recommend should be addressed.

As for the press and politicians, the overwhelming evidence is that relations on a day-to-day basis are in robust good health and performing the vital public interest functions of a free press in a vigorous democracy; everyday interactions between journalists and politicians cause no concern. But senior politicians across the spectrum have accepted that in a number of respects the relationship between politics and the press has been ‘too close’. I agree.

What I am concerned about is a particular kind of lobbying, conducted out of the public eye, through the relationships of policy makers and those in the media who stand to gain or lose from the policy being considered. That gives rise to the understandable perception that the power of the press to affect political fortunes may be used to influence that policy. This, in turn, undermines public trust and confidence in decisions on media matters being taken genuinely in the public interest. This is a long-standing issue, and one which, over the years and across the political spectrum, has repeatedly resulted in opportunities being missed to respond appropriately to legitimate public concern about press behaviour.

The press is, of course, entitled to lobby in its own interests, whether editorially or through the senior political access it enjoys. It is, however, the responsibility of the politicians to ensure that the decisions that are taken are seen to be based on the public interest as a whole. This means the extent to which they are lobbied by the press should be open and transparent; and that the public should therefore have a basic understanding of the process. In this limited area, I have recommended that consideration should be given to a number of steps to create greater transparency about these influential relationships at the top of politics and the media and so address the issue of public perception and hence trust and confidence. A good start would be for those steps towards greater transparency to be taken in relation to press lobbying about this Report.

Similar considerations apply to the role of Ministers when taking decisions about the public interest in relation to media ownership. I believe that democratically accountable Ministers are the right people to make these decisions. However, I have made recommendations as to how the process can be made much more transparent to ensure that in future there should be no risk even of the perception of bias. It is essential that the UK retains a plural media with a genuine diversity of ownership, approach and perspective. In my opinion, the competition authorities should have the means to keep levels of plurality under review and be equipped with a full range of remedies to deal with concerns.

I must now place on record my thanks to all those who participated in the Inquiry.These are the assessors who have advised in areas of their expertise and who were selected by the Government with the support of the Leader of the Opposition, in the Prime Minister’s words “for their complete independence from all interested parties”; Robert Jay and counsel, for collating and presenting such a massive volume of evidence so efficiently; everyone in the Inquiry team who has worked so hard to achieve so much in such limited time; the core participants and their lawyers; and, most of all, the public who have provided evidence, views and submissions.

As I said at the beginning, this is the seventh time in less than 70 years that these issues have been addressed. No-one can think it makes any sense to contemplate an eighth. I hope that my recommendations will be treated in exactly the same cross party spirit which led to the setting up of the Inquiry in the first place and will lead to a cross party response. I believe that the Report can and must speak for itself; to that end, I will be making no further comment. Nobody will be speaking for me about its contents either now or in the future. The ball moves back into the politicians’ court: they must now decide who guards the guardians.

The Report has been published at http://www.official-documents.gov.uk/document/hc1213/hc07/0780/0780.asp

The Executive Summary has been published at http://www.official-documents.gov.uk/document/hc1213/hc07/0779/0779.asp

A copy of Lord Justice Leveson’s statement has been published at Remarks by Lord Justice Leveson – 29 November 2012 (pdf, 36KB)