JAN LOKPAL CAMPAIGN

DEPARTMENT RELATED PARLIAMENTARY STANDING COMMITTEE ON PERSONNEL, PUBLIC GRIEVANCES, LAW AND JUSTICE FORTY EIGHTH REPORT ON THE LOKPAL BILL, 2011

1. In a nut shell, therefore, this Committee could become legally operational only w.e.f. September 23, 2011 and has completed hearing witnesses on 4th November, 2011. It had its total deliberations including Report adoption spread over 14 meetings, together aggregating 40 hours within the space of ten weeks commencing from September 23, 2011 and ending December 7, 2011. [Para 2.6.]

2. Though not specific to this Committee, it is an established practice that all 24 Parliamentary Standing Committees automatically lapse on completion of their one year tenure and are freshly constituted thereafter. This results in a legal vacuum, each year, of approximately two to three weeks and occasionally, as in the present case, directly affects the urgent and ongoing business of the Committee. The Committee would respectfully request Parliament to reconsider the system of automatic lapsing. Instead, continuity in Committees but replacement of Members on party-wise basis would save time. [Para 2.7.]

The Concept of Lokpal: Evolution and Parliamentary History

3. A proposal in this regard was first initiated in the Lok Sabha on April 3, 1963 by the Late Dr. LM Singhvi, MP2. While replying to it, the then Law Minister observed that though the institution seemed full of possibilities, since it involved a matter of policy, it was for the Prime Minister to decide in that regard3. Dr. LM Singhvi then personally communicated this idea to the then Prime Minister, Pandit Jawahar Lal Nehru who in turn, with some initial hesitation, acknowledged that it was a valuable idea which could be incorporated in our institutional framework. On 3rd November, 1963, Hon’ble Prime Minister made a statement in respect of the possibilities of this institution and said that the system of Ombudsman fascinated him as the Ombudsman had an overall authority to deal with the charges of corruption, even against the Prime Minister, and commanded the respect and confidence of all4. [Para 3.3]

4. Thereafter, to give effect to the recommendations of the First Administrative Reforms Commission, eight Bills were introduced in the Lok Sabha from time to time. However, all these Bills lapsed consequent upon the dissolution of the respective Lok Sabhas, except in the case of the 1985 Bill which was subsequently withdrawn after its introduction. A close analysis of the Bills reflects that there have been varying approaches and shifting foci in scope and jurisdiction in all these proposed legislations. The first two Bills viz. of 1968 and of 1971 sought to cover the entire universe of bureaucrats, Ministers, public sector undertakings, Government controlled societies for acts and omissions relating to corruption, abuse of position, improper motives and maladministration.The 1971 Bill, however, sought to exclude the Prime Minister from its coverage. The 1977 Bill broadly retained the same coverage except that corruption was subsequently sought to be defined in terms of IPC and Prevention of Corruption Act. Additionally, the 1977 Bill did not cover maladministration as a separate category, as also the definition of “public man” against whom complaints could be filed did not include bureaucrats in general. Thus, while the first two Bills sought to cover grievance redressal in respect of maladministration in addition to corruption, the 1977 version did not seek to cover the former and restricted itself to abuse of office and corruption by Ministers and Members of Parliament. The 1977 Bill covered the Council of Ministers without specific exclusion of the Prime Minister. The 1985 Bill was purely focused on corruption as defined in IPC and POCA and neither sought to subsume mal-administration or mis-conduct generally nor bureaucrats within its ambit. Moreover, the 1985 Bill impliedly included the Prime Minister since it referred to the office of a Minister in its definition of “public functionary”.

The 1989 Bill restricted itself only to corruption, but corruption only as specified in the POCA and did not mention IPC. It specifically sought to include the Prime Minister, both former and incumbent.

Lastly, the last three versions of the Bill in 1996, 1998 and 2001, all largely;

(a) focused only on corruption;

(b) defined corruption only in terms of POCA;

(c) defined “public functionaries” to include Prime Minister, Ministers and MPs;

(d) did not include bureaucrats within their ambit. [Para 3.5]

5. Though the institution of Lokpal is yet to become a reality at the Central level, similar institutions of Lokayuktas have in fact been setup and are functioning for many years in several States. In some of the States, the institution of Lokayuktas was set up as early as in 1970s, the first being Maharashtra in 1972. Thereafter, State enactments were enacted in the years 1981 (M.P.), 1983 (Andhra Pradesh and Himachal Pradesh), 1984 (Karnataka), 1985 (Assam), 1986 (Gujarat), 1995 (Delhi), 1999 (Kerala), 2001 (Jharkhand), 2002 (Chhatisgarh) and 2003 (Haryana). At present, Lokayuktas are in place in 17 States and one Union Territory. However, due to the difference in structure, scope and jurisdiction, the effectiveness of the State Lokayuktas vary from State to State. It is noteworthy that some States like Gujarat, Karnataka, Bihar, Rajasthan and Andhra Pradesh have made provisions in their respective State Lokayuktas Act for suo motu investigation by the Lokpal. In the State Lokayukta Acts of some States, the Lokayukta has been given the power for prosecution and also power to ensure compliance of its recommendations. However, there is a significant difference in the nature of provisions of State Acts and in powers from State to State. Approximately nine States in India have no Lokayukta at present. Of the States which have an enactment, four States have no actual appointee in place for periods varying from two months to eight years. [Para 3.8]

Citizens’ Charter and Grievance Redressal Mechanism

6. The Committee believes that while providing for a comprehensive Grievance Redressal Mechanism is absolutely critical, it is equally imperative that this mechanism be placed in a separate framework which ensures speed, efficiency and focus in dealing with citizens’ grievances as per a specified Citizens’ Charter.

The humongous number of administrative complaints and grievance redressal requests would critically and possibly fatally jeopardize the very existence of a Lokpal supposed to battle corruption. At the least, it would severally impair its functioning and efficiency. Qualitatively, corruption and mal-administration fall into reasonably distinct watertight and largely non-overlapping, mutually exclusive compartments. The approach to tackling such two essentially distinct issues must necessarily vary in content, manpower, logistics and structure. The fact that this Committee recommends that there must be a separate efficacious mechanism to deal with Grievance Redressal and Citizens’ Charter in a comprehensive legislation other than the Lokpal Bill does not devalue or undermine the vital importance of that subject. [Para 4.15]

7. Consequently the Committee strongly recommends the creation of a separate comprehensive enactment on this subject and such a Bill, if moved through the Personnel/Law Ministry and if referred to this Standing Committee, would receive the urgent attention of this Committee. Indeed, this Committee, in its 29th Report on “Public Grievance Redressal Mechanism”, presented to Parliament in October, 2008 had specifically recommended the enactment of such a mechanism. [Para 4.16]

8. To emphasize the importance of the subject of Citizens’ Charter and to impart it the necessary weight and momentum, the Committee is of the considered opinion that any proposed legislation on the subject:

(i) should be urgently undertaken and be comprehensive and all inclusive;

(ii) such enactment should, subject to Constitutional validity, also be applicable for all States as well in one uniform legislation;

(iii) must provide for adequate facilities for proper guidance of the citizens on the procedural and other requirements while making requests.

(iv) must provide for acknowledgement of citizen’s communications within a fixed time frame;

(v) must provide for response within stipulated time frame;

(vi) must provide for prevention of spurious or lame queries from the department concerned to illegally/unjustifiably prolong/extend the time limit for response;

(vii) must provide for clearly identifiable name tags for each employee of different Government departments;

(viii) must provide for all pending grievances to be categorized subject-wise and notified on a continually updated website for each department;

(ix) must provide for a facilitative set of procedures and formats, both for complaints and for appeals on this subject – along the lines of the Information Commissioners system set up under the RTI;

(x) must, in the event that the proposed Central law does not cover states, make strong recommendations to have similar enactments for grievance redressal/citizen charter at each State level;

(xi) may provide for exclusionary or limited clauses in the legislation to the effect that Citizen Charter should not include services involving constraints of supply e.g. power, water, etc. but should include subjects where there is no constraint involved e.g. birth certificates, decisions, assessment orders. These two are qualitatively different categories and reflect an important and reasonable distinction deserving recognition without which Government departments will be burdened with the legal obligation to perform and provide services or products in areas beyond their control and suffering from scarcity of supply. [Para 4.17]

9. The Committee strongly feels that the harmonious synchronization of the RTI Act and of the Citizens’ Charter and Public Grievances Redressal Mechanism will ensure greater transparency and accountability in governance and enhance the responsiveness of the system to the citizens’ Needs/expectations/grievances. [Para 4.18]

10. Lastly, the Committee wishes to clarify that the conclusion of the Hon’ble Union Minister for Finance on the Floor of the House quoted in Para 1.8 above of the Report does not intend to direct or mandate or bind or oblige this Committee to provide for a Citizen’s Charter within the present Lokpal Bill alone. The Committee reads the quoted portion in para 1.8 above to mean and agree in principle to provide for a Citizen’s Charter/Grievance Redressal system but not necessarily and inexorably in the same Lokpal Bill. Secondly, the reference to ‘appropriate mechanism’ in para 1.8 above further makes it clear that there must be a mechanism dealing with the subject but does not require it to be in the same Lokpal Bill alone. Thirdly, the reference in para 1.8 above to the phrase ‘under Lokpal’ is not read by the Committee to mean that such a mechanism must exist only within the present Lokpal Bill. The Committee reads this to mean that there should be an appropriate institution to deal with the subject of Citizen’s Charter/Grievance redressal which would be akin to the Lokpal and have its features of independence and efficacy, but not that it need not be the very same institution i.e. present Lokpal. Lastly, the Committee also takes note of the detailed debate and divergent views of those who spoke on the Floor of both Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha on this issue and concludes that no binding consensus or resolution to the effect that the Grievances Redressal/Citizen’s Charter mechanism must be provided in the same institution in the present Lokpal Bill, has emerged [Para 4.19]

11. Contextually, the issues and some of the suggestions in this Chapter may overlap with and should, therefore, be read in conjunction with Chapter 13 of this report. Though the Committee has already opined that the issue of grievance redressal should be dealt with in a separate legislation, the Committee hereby also strongly recommends that there should be a similar declaration either in the same Chapter of the Lokpal or in a separate Chapter proposed to be added in the Indian Constitution, giving the same constitutional status to the citizens grievances and redressal machinery.[Para 4.20]

12. This recommendation to provide the proposed Citizen Charter and Grievances Redressal Machinery the same Constitutional status as the Lokpal also reflects the genuine and deep concern of this Committee about the need, urgency, status and importance of a citizen’s charter/grievance machinery. The Committee believes that the giving of the aforesaid constitutional status to this machinery would go a long way in enhancing its efficacy and in providing a healing touch to the common man. Conclusions and recommendations in this regard made in para 13.12 (j) and (k) should be read in conjunction herein.[Para 4.21]

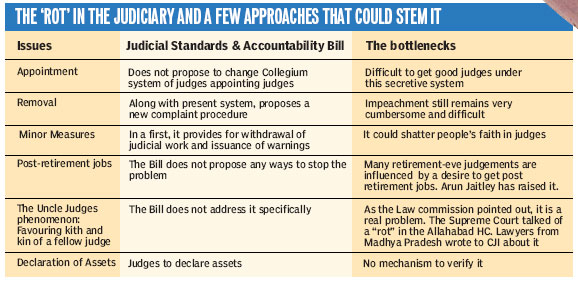

13. Furthermore, the Committee believes that this recommendation herein is also fully consistent with the letter and spirit of para 1.8 above viz. the conclusions of the Minister of Finance in the Lower House recorded in para 1.8 above. [Para 4.22]

The Prime Minister : Full Exlusion Versus Degrees of Inclusion

14. The issue of the Prime Minister’s inclusion or exclusion or partial inclusion or partial exclusion has been the subject of much debate in the Committee. Indeed, this has occupied the Committee’s deliberations for at least three different meetings. Broadly, the models / options which emerged are as follows:

(a) The Prime Minister should be altogether excluded, without exception and without qualification.

(b) The Prime Minister should altogether be included, without exception and without qualification ( though this view appears to be that of only one or two Members).

(c) The Prime Minister should be fully included, with no exclusionary caveats but he should be liable to action / prosecution only after demitting office.

(d) The Prime Minister should be included, with subject matter exclusions like national security, foreign affairs, atomic energy and space. Some variants and additions suggested included the addition of “national interest” and “public order” to this list of subject matter exclusions.

(e) One learned Member also suggested that the Prime Minister be included but subject to the safeguard that the green signal for his prosecution must be first obtained from either both Houses of Parliament in a joint sitting or some variation thereof. [Para 5.22]

15. It may be added that so far as the deferred prosecution model is concerned, the view was that if that model is adopted, there should be additional provisions limiting such deferment to one term of the Prime Minister only and not giving the Prime Minister the same benefit of deferred prosecution in case the Prime Minister is re-elected. [Para 5.23]

16. In a nut shell, as far as the overwhelming number of Members of the Committee are concerned, it was only three models above viz. as specified in paras (a), (c) and (d) in para 5.17 above which were seriously proposed. [Para 5.24]

17. Since the Committee finds that each of the views as specified in paras (a), (c) and (d) in para 5.17 above had reasonably broad and diverse support without going into the figures for or against or into the names of individual Members, the Committee believes that, in fairness, all these three options be transmitted by the Committee as options suggested by the Committee, leaving it to the good sense of Parliament to decide as to which option is to be adopted. [Para 5.25]

18. It would be, therefore, pointless in debating the diverse arguments in respect of each option or against each option. In fairness, each of the above options has a reasonable zone of merit as also some areas of demerit. The Committee believes that the wisdom of Parliament in this respect should be deferred to and the Committee, therefore, so opines. [Para 5.26]

Members of Parliament: Vote, Speech and Conduct within the House

19. The Committee strongly feels that constitutional safeguards given to MPs under Article 105 are sacrosanct and time-tested and in view of the near unanimity in the Committee and among political parties on their retention, there is no scope for interfering with these provisions of the Constitution. Vote, conduct or speech within the House is intended to promote independent thought and action, without fetters, within Parliament. Its origin, lineage and continuance is ancient and time-tested. Even an investigation as to whether vote, speech or conduct in a particular case involves or does not involve corrupt practices, would whittle such unfettered autonomy and independence within the Houses of Parliament down to vanishing point. Such immunity for vote, speech or conduct within the Houses of Parliament does not in any manner leave culpable MPs blameless or free from sanction. They are liable to and, have, in the recent past, suffered severe parliamentary punishment including expulsion from the Houses of Parliament, for alleged taking of bribes amounting to as little as Rs. 10,000/- for asking questions on the floor of the House. It is only external policing of speech, vote or conduct within the House that Article 105 frowns upon. It leaves such speech, vote and conduct not only subject to severe intra-parliamentary scrutiny and action, but also does not seek to affect corrupt practices or any other vote, speech or conduct outside Parliament. There is absolute clarity and continued unanimity on the necessity for this limited immunity to be retained. Hence, speculation on constitutional amendment in this regard is futile and engenders interminable delay.[Para 6.19]

20. Consequently, the existing structure, mechanism, text and context of clauses 17 (1) (c) and 17 (2) in the Lokpal Bill 2011 should be retained.[Para 6.20]

Lokpal and State Lokayuktas: Single Enactment and Uniform Standards

21. The Committee finds merit in the suggestion for a single comprehensive federal enactment dealing with Lokpal and State Lokayuktas. The availability of uniform standards across the country is desirable; the prosecution of public servants based upon widely divergent standards in neighboring states is an obvious anomaly. The Committee has given its earnest attention to the constitutional validity of a single enactment subsuming both the Lokpal and Lokayukta and concludes that such an enactment would be not only desirable but constitutionally valid, inter alia because,

(a) The legislation seeks to implement the UN Convention on Corruption ratified by India.

(b) Such implementing legislation is recognized by Article 253 and is treated as one in List III of the 7th Schedule.

(c) It gets additional legislative competence, inter-alia, individually or jointly under Entries 1, 2 and 11A of List-III.

(d) A direct example of provision for National Human Rights Commission and also for State Human Rights Commissions in the same Act is provided in the Protection of the Human Rights Act 1986 seeking to implement the UN Convention for the Protection of Human Rights.

(e) Such Parliamentary legislation under Article 253, if enacted, can provide for repealing of State Lokayukta Acts; subject, however, to the power of any State to make State specific amendments to the federal enactments after securing Presidential assent for such State specific amendments.[Para 7.26]

22. Additionally, it is recommended that the content of the provisions dealing with State Lokayuktas in the proposed central/ federal enactment must be covered under a separate chapter in the Lokpal Bill. That may be included in one or more chapters possibly after Chapter II and before Chapter III as found in the Lokpal Bill 2011. The entire Lokpal Bill 2011 would have to incorporate necessary changes and additions, mutatis mutandis, in respect of the State Lokayukta institutions. To give one out of many examples, the Selection Committee would be comprised of the State Chief Minister, the Speaker of the Lower House of the State, the Leader of Opposition in the Lower House, the Chief Justice of the High Court and a joint nominee of the State Election Commissioner, the State Auditor General and State PSC Chairman or, where one or more of such institutions is absent in the State, a joint nominee of comparable institutions having statutory status within the State.[Para 7.27]

23. All these State enactments shall include the Chief Minister within their purview. The Committee believes that the position of the State Chief Minister is not identical to that of the Prime Minister. The arguments for preventing instability and those relating to national security or the image of the country do not apply in case of a Chief Minister. Finally, while Article 356 is available to prevent a vacuum for the post of Chief Minister, there is no counterpart constitutional provision in respect of the federal Government.[Para 7.28]

24. Article 51 (c) of the Directive Principles of State Policy enjoining the federation to “foster respect for international law and treaty obligations……………..” must also be kept in mind while dealing with implementing legislations pursuant to international treaties, thus providing an additional validating basis for a single enactment.[Para 7.29]

25. The Committee recommends that the Lokpal Bill 2011 may be expanded to include several substantive provisions which would be applicable for Lokayuktas in each State to deal with issues of corruption of functionaries under the State Government and employees of those organizations controlled by the State Government, but that, unlike the Lokpal, the state Lokayuktas would cover all classes of employees.[Para 7.30]

26. The Committee recommends that if the above recommendation is implemented the Lokpal Bill 2011 may be renamed as “Lokpal and Lokayuktas Bill 2011”[Para 7.31]

27. The Committee believes that the recommendations, made herein, are fully consistent with and implement, in letter and spirit, the conclusions of the Minister of Finance on the floor of the Houses in respect of establishment of Lokayuktas in the States, as quoted in para 1.8 above. The Committee is conscious of the fact that the few States which have responded to the Secretariat’s letter sent to each and every State seeking to elicit their views, have opposed a uniform Central federal Lokpal and Lokayukta Bill and, understandably and expectedly, have sought to retain their powers to enact State level Lokayukta Acts. The Committee repeats and reiterates the reasons given hereinabove, in support of the desirability of one uniform enactment for both Lokpal and Lokayuktas. The Committee also reminds itself that if such a uniform Central enactment is passed, it would not preclude States from making any number of State specific amendments, subject to prior Presidential assent, as provided in the Indian Constitution. The Committee, therefore, believes that it has rightly addressed the two issues which arise in this respect viz. the need and desirability for a uniform single enactment and, secondly, if the latter is answered in the affirmative, that such a uniform enactment is Constitutionally valid and permissible.[Para 7.32]

28. Since this report, and especially this chapter, recommends the creation of a uniform enactment for both Central and State Lokayuktas, it is reiterated that a whole separate chapter (or, indeed, more than one chapter) would have to be inserted in the Lokpal Bill of 2011 providing for State specific issues. Secondly, this would have to be coupled with mutatis mutandis changes in other parts of the Act to accommodate the fact that the same Act is addressing the requirement of both the federal institution and also the State level institution.[Para 7.33]

29. Furthermore, each and every chapter and set of recommendations in this report should also be made applicable, mutatis mutandis, by appropriate provisions in the Chapter dealing with State Lokayuktas. [Para 7.34]

30. Although it is not possible for this Committee to specifically list the particularised version of each and every amendment or adaptation required to the Lokpal Bill, 2011 to subsume State Lokayuktas within the same enactment, it gives below a representative non-exhaustive list of such amendments/adaptations, which the Government should suitably implement in the context of one uniform enactment for both Lokpal and Lokayuktas. These include :

(a) Clause 1 (2) should be retained even for the State Lokayukta provisions since State level officers could well be serving in parts of India other than the State concerned as also beyond the shores of India.

(b) The Chief Minister must be included within the State Lokayukta on the same basis as any other Minister of the Council of Ministers at the State level. Clause 2 of the 2011 Bill must be amended to include Government servants at the State level. The competent authority in each case would also accordingly change e.g. for a Minister of the Council of Minister, it would be the Chief Minister; for MLAs, it would be the presiding officer of the respective House and so on and so forth. The competent authority for the Chief Minister would be the Governor.

(c) As regards Clause 3, the only change would be in respect of the Chairperson, which should be as per the recommendation made for the Lokpal.

(d) As regards the Selection Committee, the issue at the Lokayukta level has already been addressed above.

(e) References in the Lokpal context to the President of India shall naturally have to be substituted at the Lokayukta level by references to the Governor of the State.

(f) The demarcation of the criminal justice process into five broad areas from the initiation of complaint till its adjudication, as provided in Chapter 12, should also apply at the State Lokayukta level. The investigative agency, like the CBI, shall be the anti-corruption unit of the State but crucially, it shall be statutorily made independent by similar declarations of independence as already elaborated in the discussion in Chapter 12. All other recommendations in Chapter 12 can and should be applied mutatis mutandis for the Lokayukta.

(g) Similarly, all the recommendations in Chapter 12 in respect of departmental inquiry shall apply to the Lokayukta with changes made, mutatis mutandis, in respect of State bodies. The State Vigilance Commission/machinery would, in such cases, discharge the functions of the CVC. However, wherever wanting, similar provisions as found in the CVC Act buttressing the independence of the CVC shall be provided.

(h) The recommendations made in respect of elimination of sanction as also the other recommendations, especially in Chapter 12, relating to Lokpal, can and should be applied mutatis mutandis in respect of Lokayukta.

(i) Although no concrete fact situation exists in respect of a genuine multi- State or inter-State corruption issue, the Committee opines that in the rare and unusual case where the same person is sought to be prosecuted by two or more State machineries of two or more Lokayuktas, there should be a provision entitling the matter to be referred by either of the States or by the accused to the Lokpal at the federal level, to ensure uniformity and to eliminate turf wars between States or jurisdictional skirmishes by the accused.

(j) As already stated above, the coverage of the State Lokayukta, unlike the Lokpal, would extend to all classes of employees, including employees of state owned or controlled entities. [Para 7.35]

Lower Bureaucracy: Degrees of Inclusion

31. The Committee, therefore, recommends

(a) That for the Lokpal at the federal level, the coverage should be expanded to include Group A and Group B officers but not to include Group C and Group D.

(b) The provisions for the State Lokayuktas should contain similar counterpart reference, for purposes of coverage, of all similar categories at the State level which are the same or equivalent to Group A and Group B for the federal Lokpal. Though the Committee was tempted to provide only for enabling power for the States to include the State Lokayuktas to include the lower levels of bureaucracy like groups ‘C’ and ‘D’ at the State level, the Committee, on careful consideration, recommends that all the groups, including the lower bureaucracy at the State level and the groups equivalent with ‘C’ and ‘D’ at the State level should also be included within the jurisdiction of State Lokayuktas with no exclusion. Employees of state owned or controlled entities should also be covered.

(c) The Committee is informed by the DoPT that after the Sixth Pay Commission Report, Group-D has been/will be transposed and submerged fully in Group-C. In other words, after the implementation of the Sixth Pay Commission Report, which is already under implementation, Group-D will disappear and there will be only Group-C as far as the Central Government employees are concerned.

(i) Consequently, Group-C, which will shortly include the whole ofGroup-D will comprise a total number of approximately 30 lakhs (3million) employees. Though the figures are not fully updated, A+Bclasses recommended for inclusion by this Committee would comprise just under 3 lakhs employees. With some degree of approximation, the number of Railway employees from group A to D inclusive can be pegged at about 13½ lakhs (as on March 2010). If Central Government PSUs are added, personnel across all categories (Group A, B, C and D as existing) would be approximately an additional 15 lakhs employees. Post and Telegraph across all categories would further number approximately 4½ lakhs employees. Hence the total, on the aforesaid basis (which is undoubtedly an approximation and a 2010 figure) for Group A to D (soon, as explained above, to be only Group-C) + Railways + Central PSUs + Post and Telegraph would be approximately 63 lakhs, or at 2011 estimates, let us assume 65 lakhs i.e. 6.5 million.

(ii) On a conservative estimate of one policing officer per 200 employees (a ratio propounded by several witnesses including Team Anna), approximately 35000 employees would be required in the Lokpal to police the aforesaid group of Central Government employees (including, as explained above, Railways, Central PSUs, P&T etc.). This policing is certainly not possible by the proposed nine member Lokpal. The Lokpal would have to spawn a bureaucracy of at least 35000 personnel who would, in turn, be recruited for a parallel Lokpal bureaucracy. Such a mammoth bureaucracy, till it is created, would render the Lokpal unworkable. Even after it is created, it may lead to a huge parallel bureaucracy which would set in train its own set of consequences, including arbitrariness, harassment and unfair and illegal action by the same bureaucracy which, in the ultimate analysis would be nothing but a set of similar employees cutting across the same A, B and C categories. As some of the Members of the Committee, in a lighter vein put it, one would then have to initiate a debate on creating a super Lokpal or a Dharampal for the policing of the new bureaucracy of the Lokpal institution itself.

(iia) The Committee also notes that as far as the Lokpal institution is concerned, it is proposed as a new body and there is no such preexisting Lokpal bureaucracy available. In this respect, there is a fundamental difference between the Lokpal and Lokayuktas, the latter having functioned, in one form or the other in India for the last several decades, with a readily available structure and manpower in most parts of India.

(iii) If, from the above approximate figure of 65 lakhs, we exclude C and D categories (as explained earlier, D will soon become part of C) from Central Government, Railways, PSUs, Post and Telegraph etc., the number of A and B categories employees in these departments would aggregate approximately 7.75 lakhs. In other words, the aggregate of C and D employees in these classes aggregate approximately 57 or 58 lakhs. The Committee believes that this figure of 7.75 or 8 lakhs would be a more manageable, workable and desirable figure for the Lokpal institution, at least to start with.

(iv) The impression that inclusion of Group ‘A’ and B alone involves exclusion of large sections of the bureaucracy, must be dispelled. Though in terms of number, the aggregation of Groups ‘C’ and ‘D’ is an overwhelming percentage of total Central Government employees, Groups ‘A’ and B include the entire class above the supervisory level. Effectively, this means that virtually all Central Government employees at the Section Officer level and above would be included. It is vital to emphasize that this demarcation has to be viewed in functional terms, since it gives such categories significant decision making power in contra-distinction to mere numbers and necessarily subsumes a major chunk of medium and big ticket corruption.

(v) Another misconception needs to be clarified. There is understandable and justifiable anger that inclusion of Group C and D would mean exclusion of a particular class which has tormented the common man in different ways over the years viz. Tehsildar, Patwari and similarly named or equivalent officers. Upon checking, the Secretariat has clarified that these posts are State Government posts under gazette notification notified by the State Government and hence the earlier recommendation of this Committee will enable their full inclusion.

(vi) We further recommend that for the hybrid category of Union Territories, the same power be given as is recommended above in respect of State Lokayuktas. The Committee also believes that this is the appropriate approach since a top heavy approach should be avoided and the inclusionary ambit should be larger and higher at the state level rather than burdening the Lokpal with all classes of employees.

(vii) As of now, prior to the coming into force of the Lokpal Act or any of the recommendations of this report, Group C and D officers are not dealt with by the CVC. Group C & D employees have to be proceeded against departmentally by the appropriate Department Head, who may either conduct a departmental enquiry or file a criminal corruption complaint against the relevant employee through the CBI and/or the normal Police forces. The Committee now recommends that the entire Group C & D, (later only Group C as explained above) shall be brought specifically under the jurisdiction of the CVC. In other words, the CVC, which is a high statutory body of repute and whose selection process includes the Leader of the Opposition, should be made to exercise powers identical to or at least largely analogous, in respect of these class C and class D employees as the Lokpal does for Group A and B employees. The ultimate Lokpal Bill/Act should thus become a model for the CVC, in so far as Group C & D employees are concerned. If that requires large scale changes in the CVC Act, the same should be carried out. This would considerably strengthen the existing regime of policing, both departmentally and in terms of anti-corruption criminal prosecutions, all Group C & D employees and would not in any manner leave them either unpoliced or subject to a lax or ineffective regime of policing.

(viii) Furthermore, this Committee recommends that there would be broad supervisory fusion at the apex level by some appropriate changes in the CVC Act. The CVC should be made to file periodical reports, say every three months, to the Lokpal in respect of action taken for these class C and D categories. On these reports, the Lokpal shall be entitled to make comments and suggestions for improvement and strengthening the functioning of CVC, which in turn, shall file, appropriate action taken reports with the Lokpal.

(ix) Appropriate increase in the strength of the CVC manpower, in the light of the foregoing recommendations, would also have to be considered by the Government.

(x) The Committee also feels that this is the start of the Lokpal institution and it should not be dogmatic and inflexible on any of the issues. For a swift and efficient start, the Lokpal should be kept slim, trim, effective and swift. However, after sometime, once the Lokpal institution has stabilized and taken root, the issue of possible inclusion of Group C classes also within the Lokpal may be considered. This phase-wise flexible and calibrated approach would, in the opinion of this Committee, be more desirable instead of any blanket inclusion of all classes at this stage.

(xi) Another consideration which the Committee has kept in mind is the fact that if all the classes of higher, middle and lower bureaucracy are included within the Lokpal at the first instance itself, in addition to all the aforesaid reasons, the CVC’s role and functioning would virtually cease altogether, since the CVC would have no role in respect of any class of employee and would be reduced, at best, to a vigilance clearance authority. This would be undesirable in the very first phase of reforms, especially since the CVC is a high statutory authority in this country which has, over the last half century, acquired a certain institutional identity and stability along with conventions and practices which ought not to be uprooted in this manner.

(d) All provisions for prior sanction / prior permission, whether under the CrPC or Prevention of Corruption Act or DSPE Act or related legislation must be repealed in respect of all categories of bureaucrats / government servants, whether covered by the Lokpal or not, and there should consequently be no requirement of sanction of any kind in respect of any class or category of officers at any level in any Lokpal and Lokayukta or , indeed, CVC proceedings ( for non Lokpal covered categories). In other words, the requirement of sanction must go not only for Lokpal covered personnel but also for non-Lokpal covered personnel i.e. class ‘C’ and ‘D’ (Class D, as explained elsewhere, will eventually be submerged into Class ‘C’). The sanction requirement, originating as a salutary safeguard against witch hunting has, over the years, as applied by the bureaucracy itself, degenerated into a refuge for the guilty, engendering either endless delay or obstructing all meaningful action. Moreover, the strong filtering mechanism at the stage of preliminary inquiry proposed in respect of the Lokpal, is a more than adequate safeguard, substituting effectively for the sanction requirement.

(e) No doubt corruption at all levels is reprehensible and no doubt corruption at the lowest levels does affect the common man and inflicts pain and injury upon him but the Committee, on deep consideration and reconsideration of this issue, concluded that this new initiative is intended to send a clear and unequivocal message, first and foremost, in respect of medium and big ticket corruption. Secondly, this Committee is not oblivious to the fact that jurisdiction to cover the smallest Government functionary at the peon and driver level ( class C largely covers peons, assistants, drivers, and so on, though it does also cover some other more “powerful” posts) may well provide an excuse and a pretext to divert the focus from combating medium and big ticket corruption to merely catching the smaller fry and building up an impressive array of statistical prosecutions and convictions without really being able to root out the true malaise of medium and big ticket corruption which has largely escaped scrutiny and punishment over the last 60 years.

(f) The Committee also believes that the recommendations in respect of scope of coverage of the lower bureaucracy, made herein, are fully consistent with the conclusions of the Minister of Finance on the floor of the Houses, as quoted in para 1.8 above of this Report. Firstly, the lower bureaucracy has been, partly, brought within the coverage as per the recommendations above and is, thus, consistent with the essence of the conclusion contained in para 1.8 above. Secondly, the Committee does not read para 1.8 above to meet an inevitable and inexorable mandate to necessarily subsume each and every group of civil servant (like Group ‘C’ or Group ‘D’, etc.). Thirdly, the in principle consensus reflected in para 1.8 would be properly, and in true letter and spirit, be implemented in regard to the recommendations in the present Chapter for scope and coverage of Lokpal presently. Lastly, it must be kept in mind that several other recommendations in this Report have suggested substantial improvements and strengthening of the provisions relating to policing of other categories of personnel like C and D, inter alia, by the CVC and/or to the extent relevant, to be dealt with as Citizens’ Charter and Grievance Redressal issues.[Para 8.18]

False Complaints and Complainants: Punitive Measures

32.. It cannot be gainsaid that after the enormous productive effort put in by the entire nation over the last few months for the creation of a new initiative like the Lokpal Bill, it would not and cannot be assumed to be anyone’s intention to create a remedy virtually impossible to activate, or worse in consequence than the disease. The Committee, therefore, starts with the basic principle that it must harmoniously balance the legitimate but competing demands of prevention of false, frivolous complaints on the one hand as also the clear necessity of ensuring that no preclusive bar arises which would act as a deterrent for genuine and bona fide complaints.[Para 9.6]

33. The Committee sees the existing provisions in this regard as disproportionate, to the point of being a deterrent.[Para 9.7]

34. The Committee finds a convenient analogous solution and therefore adopts the model which the same Committee has adopted in its recently submitted report on Judicial Standards and Accountability Bill, 2010 presented to the Rajya Sabha on August 30, 2011.[Para 9.8]

35. In para 18.8 of the aforesaid Report, the Committee, in the context of Judicial Standards and Accountability Bill, 2010 said : “The Committee endorses the rationale of making a provision for punishment for making frivolous or vexatious complaints. The Committee, however, expresses its reservation over the prescribed quantum of punishment both in terms of imprisonment which is up to 5 years and fine which is up to 5 lakh rupees. The severe punishment prescribed in the Bill may deter the prospective complainants from coming forward and defeat the very rationale of the Bill. In view of this, the Committee recommends that Government should substantially dilute the quantum of the punishment so as not to discourage people from taking initiatives against the misbehaviour of a judge. In any case, it should not exceed the punishment provided under the Contempt of Court Act. The Government may also consider specifically providing in the Bill a proviso to protect those complainants from punishment / penalty who for some genuine reasons fail to prove their complaints. The Committee, accordingly, recommends that the Bill should specifically provide for protection in case of complaints made ‘in good faith’ in line with the defence of good faith available under the Indian Penal Code.” [Para 9.9]

36. Consequently, in respect of the Lokpal Bill, the Committee recommends that, in respect of false and frivolous complaints, :

(a) The punishment should include simple imprisonment not exceeding six months;

(b) The fine should not exceed Rs.25000; and

(c) The Bill should specifically provide for protection in case of complaints made in good faith in line with the defence of good faith available under the Indian Penal Code under Section 52 IPC.[Para 9.10]

The Judiciary: To Include or Exclude

37. The Committee recommends:

(i) The Judiciary, comprising 31 odd judges of the Apex Court, 800 odd judges of the High Courts, and 20,000 odd judges of the subordinate judiciary are a part of a separate and distinct organ of the State. Such separation of judicial power is vitally necessary for an independent judiciary in any system and has been recognized specifically in Article 50 of the Indian Constitution. It is interesting that while the British Parliamentary democratic system, which India adopted, has never followed the absolute separation of powers doctrine between the Legislature and the Executive, as, for example, found in the US system, India has specifically mandated under its Constitution itself that such separation must necessarily be maintained between the Executive and the Legislature on the one hand and the Judiciary on the other.

(ii) Such separation, autonomy and necessary isolation is vital for ensuring an independent judicial system. India is justifiably proud of a vigorous (indeed sometimes over vigorous) adjudicatory judicial organ. Subjecting that organ to the normal process of criminal prosecution or punishment through the normal courts of the land would not be conducive to the preservation of judicial independence in the long run.

(iii) If the Judiciary were included simpliciter as suggested in certain quarters, the end result would be the possible and potential direct prosecution of even an apex Court Judge before the relevant magistrate exercising the relevant jurisdiction. The same would apply to High Court Judges. This would lead to an extraordinarily piquant and an untenable situation and would undermine judicial independence at its very root.

(iv) Not including the Judiciary under the present Lokpal dispensation does not in any manner mean that this organ should be left unpoliced in respect of corruption issues. This Committee has already proposed and recommended a comprehensive Judicial Standards and Accountability Bill which provides a complete in-house departmental mechanism, to deal with errant judicial behavior by way of censure, warning, suspension, recommendation or removal and so on within the judicial fold itself. The Committee deprecates the criticism of the Judicial Standards and Accountability Bill as excluding issues of corruption for the simple reason that they were never intended to be addressed by that Bill and were consciously excluded.

(v) As stated in para 21 of the report of this Committee on the Judicial Standards and Accountability Bill, to this report, the Committee again recommends, in the present context of the Lokpal Bill, that the entire appointment process of the higher judiciary needs to be revamped and reformed. The appointment process cannot be allowed and should not be allowed to continue in the hands of a self-appointed common law mechanism created by judicial order operating since the early 1990s. A National Judicial Commission must be set up to create a broad-based and comprehensive model for judicial appointments, including, if necessary, by way of amendment of Articles 124 and 217 of the Indian Constitution. Without such a fundamental revamp of the appointment process at source and at the inception, all other measures remain purely ex-post facto and curative. Preventive measures to ensure high quality judicial recruitment at the entrance point is vital.

(vi) It is the same National Judicial Commission which has to be entrusted with powers of both transfer and criminal prosecution of judges for corruption. If desired, by amending the provisions of the Constitution as they stand today, such proposed National Judicial Commission may also be given the power of dismissal / removal. In any event, this mechanism of the National Judicial Commission is essential since it would obviate allegations and challenges to the validity of any enactment dealing with judges on the ground of erosion or impairment of judicial independence. Such judicial independence has been held to be part of the basic structure of the Indian Constitution and is therefore unamendable even by way of an amendment of the Indian Constitution. It is for this reason that while this Committee is very categorically and strongly of the view that there should be a comprehensive mechanism for dealing with the trinity of judicial appointments, judicial transfers and criminal prosecution of judges, it is resisting the temptation of including them in the present Lokpal Bill. The Committee, however, exhorts the appropriate departments, with all the power at its command, to expeditiously bring a Constitutional Amendment Bill to address the aforesaid trinity of core issues directly impinging on the judicial system today viz. appointment of high quality and high caliber judges at the inception, non-discriminatory and effective transfers and fair and vigorous criminal prosecution of corrupt judges without impairing or affecting judicial independence.

(vii) The Committee finds no reason to exclude from the conclusions on this subject, the burgeoning number of quasi-judicial authorities including tribunals as also other statutory and non-statutory bodies which, where not covered under category ‘A’ and ‘B’ bureaucrats, exercise quasijudicial powers of any kind. Arbitrations and other modes of alternative dispute resolution should also be specifically covered in this proposed mechanism. They should be covered in any eventual legislation dealing with corruption in the higher judiciary. The Committee notes that a large mass of full judicial functions, especially from the High Courts has, for the last 30 to 40 years, been progressively hived off to diverse tribunals exercising diverse powers under diverse statutory enactments. The Committee also notes that apart from and in addition to such tribunals, a plethora of Government officials or other persona designata exercise quasi judicial powers in diverse situations and diverse contexts. Whatever has been said in respect of the judiciary in this chapter should, in the considered opinion of this Committee, be made applicable, with appropriate modifications in respect of quasi-judicial bodies, tribunals and persons as well. [Para 10.21]

The Lokpal: Search and Selection

38. To ensure flexibility, speed and efficiency on the one hand and representation to all organs of State on the other, the Committee recommends a Selection Committee comprising:-

(a) The Prime Minister of India- as Head of the Executive.

(b) The Speaker Lok Sabha, as Head of the Legislature.

(c) The Chief Justice of India-as Head of the Judiciary.

(d) The leader of the Opposition of the Lower House.

(e) An eminent Indian, selected as elaborated in the next paragraph.

N.B.: functionaries like the Chairman and Leader of the Opposition of the Upper House have not been included in the interests of compactness and flexibility. The Prime Minister would preside over the Selection Committee. [Para 11.18]

39. The 5th Member of the Selection Committee in (e) above should be a joint nominee selected jointly by the three designated Constitutional bodies viz., the Comptroller and Auditor General of India, the Chief Election Commissioner and the UPSC Chairman. This ensures a reasonably wide and representative degree of inputs from eminent Constitutional bodies, without making the exercise too cumbersome. Since the other Members of the Selection Committee are all exofficio, this 5th nominee of the aforesaid Constitutional bodies shall be nominated for a fixed term of five years. Additionally, it should be clarified that he should be an eminent Indian and all the diverse criteria, individually, jointly or severally, applicable as specified in Clause 4 (1) (i) of the Lokpal Bill 2011 should be kept in mind by the aforesaid three designated Constitutional nominators.[Para 11.19]

40. There should, however, be a proviso in Clause 4(3) to the effect that a Search Committee shall comprise at least seven Members and shall ensure representation 50 per cent to Members of SC’s and/or STs and/or Other Backward Classes and/or Minorities and/or Women or any category or combination thereof. Though there is some merit in the suggestion that the Search Committee should not be mandatory since, firstly, the Selection Committee may not need to conduct any search and secondly, since this gives a higher degree of flexibility and speed to the Selection Committee, the Committee, on deep consideration, finally opines that the Search Committee should be made mandatory. The Committee does so, in particular, in view of the high desirability of providing representation in the Search Committee as stated above which, this Committee believes, cannot be effectively ensured without the mandatory requirement to have a Search Committee. It should, however, be clarified that the person/s selected by the Search Committee shall not be binding on the Selection Committee and secondly, that, where the Selection Committee rejects the recommendations of the Search Committee in respect of any particular post, the Selection Committee shall not be obliged to go back to the Search Committee for the same post but would be entitled to proceed directly by itself. [ Para 11.20]

41. Over the years, there has been growing concern in India that the entire mass of statutory quasi judicial and other similar tribunals, bodies or entities have been operated by judicial personnel i.e. retired judges, mainly of the higher judiciary viz. the High Courts and the Supreme Court.[Para 11.20(A)]

42. There is no doubt that judicial training and experience imparts not only a certain objectivity but a certain technique of adjudication which, intrinsically and by training, is likely to lead to greater care and caution in preserving principles like fair play, natural justice, burden of proof and so on and so forth. Familiarity with case law and knowledge of intricate legal principles, is naturally available in retired judicial personnel of the higher judiciary.[Para11.20(B)]

43. However, when a new and nascent structure like Lokpal is being contemplated, it is necessary not to fetter or circumscribe the discretion of the appointing authority. The latter is certainly entitled to appoint judges to the Lokpal, and specific exclusion of judges is neither contemplated nor being provided. However, to consider, as the Lokpal Bill 2011 does, only former Chief Justices of India or former judges of the Supreme Court as the Chairperson of the Lokpal would be a totally uncalled for and unnecessary fetter. The Committee, therefore, recommends that clause 3(2) be suitably modified not to restrict the Selection Committee to selecting only a sitting or former Chief Justice of India or judge of the Supreme Court as Chairperson of the Lokpal.[Para 11.20(C)]

44. A similar change is not suggested in respect of Members of the Lokpal and the existing provision in clause 3 (2) (b) read with clause 19 may continue. Although the Committee does believe that it is time to consider tribunals staffed by outstanding and eminent Indians, not necessarily only from a pool of retired members of the higher judiciary, the Committee feels hamstrung by the Apex Court decision in L. Chandra Kumar v. Union of India 1997 (3) SCC 261 which has held and has been interpreted to hold that statutory tribunals involving adjudicatory functions must not sit singly but must sit in benches of two and that at least one of the two members must be a judicial member. Hence, unless the aforesaid judgment of the Apex Court in L. Chandra Kumar v. Union of India is reconsidered, the Committee refrains from suggesting corresponding changes in clause 3 (2) (b) read with clause 19, though it has been tempted to do so.[Para 11.20(D)]

45. There is merit in the suggestion that clause 3 (4) of the Lokpal Bill 2011 be further amended to clarify that a person shall not be eligible to become Chairperson or Member of Lokpal if:

(a) He/ she is a person convicted of any offence involving moral turpitude;

(b) He/ she is a person less than 45 years of age, on date of assuming office as Chairperson or Member of Lokpal;

(c) He/ she has been in the service of any Central or State Government or any entity owned or controlled by the Central or State Government and has vacated office either by way of resignation, removal or retirement within the period of 12 months prior to the date of appointment as Chairperson or Member of Lokpal.[Para 11.20(E)]

46. In clause 9 (2), the existing provision should be retained but it should be added at the end of that clause, for the purpose of clarification, that no one shall be eligible for re-appointment as Chairperson or Member of the Lokpal if he has already enjoyed a term of five years.[Para 11.20(F)]

47. The Committee has already recommended appropriate representation on the Search Committee, to certain sections of society who have been historically marginalized. The Committee also believes that although the institution of Lokpal is a relatively small body of nine members and specific reservation cannot and ought not to be provided in the Lokpal institution itself, there should be a provision added after clause 4 (5) to the effect that the Selection Committee and the Search Committee shall make every endeavour to reflect, on the Lokpal institution, the diversity of India by including the representation, as far as practicable, of historically marginalized sections of the society like SCs/ STs, OBCs, minorities and women. [Para 11.20(G)]

48. As regards clause 51 of the Lokpal Bill, 2011, the Committee recommends that the intent behind the clause be made clear by way of an Explanation to be added to the effect that the clause is not intended to provide any general exemption and that “good faith” referred to in clause 52 shall have the same meaning as provided in section 52 of the IPC.[Para 11.20(H)]

The Trinity of the Lokpal, CBI and CVC: In Search of an Equilibrium

49. (A) Whatever is stated hereinafter in these recommendations is obviously applicable only to Lokpal and Lokayukta covered personnel and offences/ misconduct, as already delineated in this Report earlier, inter alia, in Chapter 8 and elsewhere.

(B) For those outside (A) above, the existing law, except to the extent changed, would continue to apply. (Para 12.32]

50. This Chapter, in the opinion of the Committee, raises an important issue of the quality of both investigation and prosecution; the correct balance and an apposite equilibrium of 3 entities (viz. Lokpal, CBI and CVC) after creation of the new entity called Lokpal; harmonious functioning and real life operational efficacy of procedural and substantive safeguards; the correct balance between initiation of complaint, its preliminary screening/ inquiry, its further

investigation, prosecution, adjudication and punishment; and the correct harmonization of diverse provisions of law arising from the Delhi Special Police Establishment Act, the CVC Act, the proposed Lokpal Act, the IPC, CrPC and the Prevention of Corruption Act. It is, therefore, a somewhat delicate and technical task. [Para 12.33]

51. The stages of criminal prosecution of the Lokpal and Lokayukta covered persons and officers can be divided broadly into 5 stages, viz. (a) The stage of complaint, whether by a complainant or suo motu, (b) the preliminary screening of such a complaint, (c) the full investigation of the complaint and the report in that respect, (d) prosecution, if any, on the basis of the investigation and (e) adjudication, including punishment, if any.[Para 12.34]

52. The Committee recommends that the complaint should be allowed to be made either by any complainant or initiated suo motu by the Lokpal. Since, presently, the CBI also has full powers of suo motu initiation of investigation, a power which is frequently exercised, it is felt that that the same power of suo motu proceedings should also be preserved for both the CBI and the Lokpal, subject, however, to overall supervisory jurisdiction of the Lokpal over the CBI, including simultaneous intimation and continued disclosure of progress of any inquiry or investigation by the CBI to the Lokpal, subject to what has been elaborated in the next paragraph.[Para 12.35]

53. Once the complaint, through any party or suo motu has arisen, it must be subject to a careful and comprehensive preliminary screening to rule out false, frivolous and vexatious complaints. This power of preliminary inquiry must necessarily vest in the Lokpal. However, in this respect, the recommendations of the Committee in para 12.36(I) should be read with this para. This is largely covered in clause 23 (1) of the Lokpal Bill, 2011. However, in this respect, the Lokpal would have to be provided, at the inception, with a sufficiently large internal inquiry machinery. The Lokpal Bill, 2011 has an existing set of provisions (Clauses 13 and 14 in Chapter III) which refers to a full-fledged investigation wing. In view of the structure proposed in this Chapter, there need not be such an investigation wing but an efficacious inquiry division for holding the preliminary inquiry in respect of the complaint at the threshold. Preliminary inquiry by the Lokpal also semantically distinguishes itself from the actual investigation by the CBI after it is referred by the Lokpal to the CBI. The pattern for provision of such an inquiry wing may be similar to the existing structure as provided in Chapter III of the Lokpal Bill 2011 but with suitable changes made, mutatis mutandis, and possible merger of the provisions of Chapter VII with Chapter III.[Para 12.36]

54. The Committee is concerned at the overlap of terminology used and procedures proposed, between preliminary inquiry by the Lokpal as opposed to investigation by the investigating agency, presently provided in Clause 23 of the Lokpal Bill. The Committee, therefore, recommends:

(a) that only two terms be used to demarcate and differentiate between the preliminary inquiry to be conducted by the Lokpal, inter-alia, under Chapters VI and VII read with Clause 2(1)(e) as opposed to an investigation by the investigating agency which has been proposed to be the CBI in the present report. Appropriate changes should make it clear that the investigation (by the CBI as recommended in this report), shall have the same meaning as provided in Clause 2 (h) of the Cr.P.C whereas the terms “inquiry” or “preliminary investigation” should be eschewed and the only two terms used should be “preliminary inquiry” ( by the Lokpal) on the one hand & “investigation” (by the CBI), on the other.

(b) the term preliminary inquiry should be used instead of the term inquiry in clause 2(1)(e) and it should be clarified therein that it refers to preliminary inquiry done by the Lokpal in terms of Chapters VI and VII of the Lokpal Bill, 2011 and does not mean or refer to the inquiry mentioned in Section 2(g) of the Cr.P.C.

(c) the term “investigation” alone should be used while eschewing terms like “preliminary investigation” and a similar definitional provision may be inserted after Clause 2(1)(e) to state that the term investigation shall have the same meaning as defined in Clause 2(h) of the Cr.P.C.

(d) Similar changes would have to be made in all other clauses in the Lokpal Bill, 2011, one example of which includes Clause-14.[Para 12.36(A)]

55. There are several parts of Clause 23 of the 2011 Bill, including Clauses 23(4), 23(5), 23(6), 23(9) and 23(11) which require an opportunity of being heard to be given to the public servant during the course of the preliminary inquiry i.e. the threshold proceedings before the Lokpal in the sense discussed above. After deep consideration, the Committee concludes that it is unknown to criminal law to provide for hearing to the accused at the stage of preliminary inquiry by the appropriate authority i.e. Lokpal or Lokayukta in this case. Secondly, the preliminary inquiry is the stage of verification of basic facts regarding the complaint, the process of filtering out false, frivolous, fictitious and vexatious complaints and the general process of seeing that there is sufficient material to indicate the commission of cognizable offences to justify investigation by the appropriate investigating agency. If the material available in the complaint at the stage of its verification through the preliminary inquiry is fully disclosed to the accused, a large part of the entire preliminary inquiry, later investigation, prosecution and so on, may stand frustrated or irreversibly prejudiced at the threshold. Thirdly, and most importantly, the preliminary inquiry is being provided as a threshold filter in favour of the accused and is being entrusted to an extremely high authority like the Lokpal, created after a rigorous selection procedure. Other agencies like the CBI also presently conduct preliminary inquiries but do not hear or afford natural justice to the accused during that process. Consequently the Committee recommends that all references in Clause 23 or elsewhere in the Lokpal Bill, 2011 to hearing of the accused at the preliminary inquiry stage should be deleted.[Para 12.36(B)]

56. Since the Committee has recommended abolition of the personal hearing process before the Lokpal during the preliminary inquiry, the Committee deems it fit and proper to provide for the additional safeguard that the decision of the Lokpal at the conclusion of the preliminary inquiry to refer the matter further for investigation to the CBI, shall be taken by a Bench of the Lokpal consisting of not less than 3 Members which shall decide the issue regarding reference to investigation, by a majority out of these three.[Para 12.36.(BB)]

57. Naturally it should also be made clear that the accused is entitled to a full hearing before charges are framed. Some stylistic additions like referring to the charge sheet “if any” (since there may or may not be a chargesheet) may also be added to Clause 23(6). Consequently, Clauses like 23(7) and other similar clauses contemplating proceedings open to public hearing must also be deleted. [Para 12.36(C)]

58. Clause 23(8) would have to be suitably modified to provide that the appropriate investigation period for the appropriate investigating agency i.e. CBI in the present case, should normally be within six months with only one extension of a further six months, for special reasons. Reference in Clause 23(8) to “inquiry” creates highly avoidable confusion and it should be specified that the meanings assigned to inquire and investigate should be as explained above.[Para 12.36(D)]

59. The Committee also believes that there may be several exigencies during the course of both preliminary inquiry and investigation which may lead to a violation of the 30 days or six months periods respectively specified in Clause 27(2) and 23(8). The Committee believes that it cannot be the intention of the law that where acts and omissions by the accused create an inordinate delay in the preliminary inquiry and / or other factors arise which are entirely beyond the control of the Lokpal, the accused should get the benefit or that the criminal trial should terminate. For that purpose it is necessary to insert a separate and distinct provision which states that Clauses 23(2), 23(8) or other similar time limit clauses elsewhere in the Lokpal Bill, 2011, shall not automatically give any benefit or undue advantage to the accused and shall not automatically thwart or terminate the trial. [Para 12.36(E)]

60. Clause 23(10) also needs to be modified. Presently, it states in general terms the discretion to hold or not to hold preliminary inquiry by the Lokpal for reasons to be recorded in writing. However, this may lead to allegations of pick and choose and of arbitrariness and selectivity. The Committee believes that Clause 23(10) should be amended to provide for only one definition viz., that preliminary inquiry may be dispensed with only in trap cases and must be held in all other cases. Even under the present established practice, the CBI dispenses with preliminary inquiry only in a trap case for the simple reason that the context of the trap case itself constitutes preliminary verification of the offence and no further preliminary inquiry is necessary. Indeed, for the trap cases, Section 6 A (ii) of the Delhi Special Police Establishment Act, 1946 also dispenses with the provision of preliminary inquiries. For all cases other than the trap cases, the preliminary inquiry by the Lokpal must be a non dispensable necessity.[Para 12.36(F)]

61. Clause 23(11) also needs to be modified / deleted since, in this Report, it is proposed that it is the CBI which conducts the investigation which covers and includes the process of filing the charge sheet and closure report. [Para 12.36(G)]

62. Similarly Clause 23 (12) (b) would have to be deleted, in view of the conclusion hereinabove regarding the absence of any need to provide natural justice to the accused at the stage of preliminary inquiry. Clause 23(14) is also unusually widely worded. It does not indicate as to whom the Lokpal withhold records from. Consequently that cannot be a general blanket power given to the Lokpal to withhold records from the accused or from the investigating agency. Indeed, that would be unfair, illegal and unconstitutional since it would permit selectivity as also suppress relevant information. The clause, therefore, needs to be amended.[Para 12.36(H)]

63. The case of the Lokpal initiating action suo motu, requires separate comment. In a sense, the preliminary inquiry in the case of a Lokpal suo motu action becomes superfluous since the same body ( i.e. Lokpal) which initiates the complaint, is supposed to do a preliminary inquiry. This may, however, not be as anomalous as it sounds since even under the present structure, the CBI, or indeed the local police, does both activities ie suo motu action as also preliminary screening/ inquiry. The Committee was tempted to provide for another body to do preliminary inquiry in cases where the Lokpal initiates suo motu action, but in fact no such body exists and it would create great multiplicity and logistical difficulty in creating and managing so many bodies. Hence the Committee concludes that in cases of suo motu action by Lokpal, a specific provision must provide that that part of the Lokpal which initiates the suo motu proposal, should be scrupulously kept insulated from any part of the preliminary inquiry process following upon such suo motu initiation. It must be further provided that the preliminary inquiry in cases of suo motu initiation must be done by a Lokpal Bench of not less than five Members and these should be unconnected with those who do the suo motu initiation.[Para 12.36(I)]

64. These recommendations also prevent the Lokpal from becoming a single institution fusing unto itself the functions of complainant, preliminary inquirer, full investigator and prosecutor. It increases objectivity and impartiality in the criminal investigative process and precludes the charge of creating an unmanageable behemoth like Lokpal, while diminishing the possibility of abuse of power by the Lokpal itself.[Para 12.37]

65. These recommendations also have the following advantages:

(i) The CBI’s apprehension, not entirely baseless, that it would become a Hamlet without a Prince of Denmark if its Anti-Corruption Wing was hived off to the Lokpal, would be taken care of.

(ii) It would be unnecessary to make CBI or CVC a Member of the Lokpal body itself.

(iii) The CBI would not be subordinate to the Lokpal nor its espirit de corps be adversely affected; it would only be subject to general superintendence of Lokpal. It must be kept in mind that the CBI is an over 60 year old body, which has developed a certain morale and espirit de corps, a particular culture and set of practices, which should be strengthened and improved, rather than merely subsumed or submerged within a new or nascent institution, which is yet to take root. Equally, the CBI, while enhancing its autonomy and independence, cannot be left on auto pilot.

(iv) The CVC would retain a large part of its disciplinary and functional role for non Lokpal personnel and regarding misconduct while not being subordinate to the Lokpal. However, for Lokpal covered personnel and issues, including the role of the CBI, the CVC would have no role.

(v) Mutatis mutandis statutory changes in the Lokpal Bill, the CVC and the CBI Acts and in related legislation, is accordingly recommended. [Para 12.38]

66. After the Lokpal has cleared the stage for further investigation, the matter should proceed to the CBI. This stage of the investigation must operate with the following specific enumerated statutory principles and provisions:

(A) On the merits of the investigation in any case, the CBI shall not be answerable or liable to be monitored either by the Administrative Ministry or by the Lokpal. This is also fully consistent with the established jurisprudence on the subject which makes it clear that the merits of the criminal investigation cannot be gone into or dealt with even by the superior courts. However, since in practise it has been observed in the breach, it needs to be unequivocally reiterated as a statutory provision, in the proposed Lokpal Act, a first in India.

(B) The CBI shall, however, continue to be subject to the general supervisory superintendence of the Lokpal. This shall be done by adding a provision as exists today in the CVC Act which shall now apply to the Lokpal in respect of the CBI. Consequently, the whole of the Section 8 (1) (not Section 8 (2) ) of the CVC Act should be included in the Lokpal Bill to provide for the superintendence power of the Lokpal over the CBI.[Para 12.39]

67. Correspondingly, reference in Section 4 of the Delhi Special Police Establishment Act to the CVC would have to be altered to refer to the Lokpal. [Para 12.40]

68. At this stage, the powers of the CBI would further be strengthened and enhanced by clarifying explicitly in the Lokpal Bill that all types of prior sanctions/terms or authorizations, by whatever name called, shall not be applicable to Lokpal covered persons or prosecutions. Consequently, the provisions of Section 6 (A) of the Delhi Special Police Establishment Act, Section 19 of the Prevention of Corruption Act and Section 197 of the IPC or any other provision of the law, wherever applicable, fully or partially, will stand repealed and rendered inoperative in respect of Lokpal and Lokayukta prosecutions, another first in India. Clause 27 of the Lokpal Bill, 2011 is largely consistent with this but the Committee recommends that it should further clarify that Section 6 A of the DSPE Act shall also not apply in any manner to proceedings under the proposed Act. The sanction requirement, originating as a salutary safeguard against witch hunting has, over the years, as applied by the bureaucracy itself, degenerated into a refuge for the guilty, engendering either endless delay or obstructing all meaningful action. Moreover, the strong filtering mechanism at the stage of preliminary inquiry proposed in respect of the Lokpal, is a more than adequate safeguard, substituting effectively for the sanction requirement. Elsewhere, this Report recommends that all sanction requirements should be eliminated even in respect of non Lokpal covered personnel. [Para 12.41]

69. The previous two paragraphs if implemented, would achieve genuine and declared statutory independence of investigation for the first time for the CBI.[Para 12.42]

70. The main investigation, discussed in the previous few paragraphs, to be conducted by the CBI, necessarily means the stage from which it is handed over to the CBI by the Lokpal, till the stage that the CBI files either a chargesheet or a closure report under Section 173 of the CrPC. However, one caveat needs to be added at this stage. The CBI’s chargesheet or closure report must be filed after the approval by the Lokpal and, if necessary, suitable changes may have to be made in this regard to Section 173 Cr PC and other related provisions.[Para 12.43]

71. The aforesaid independence of the CBI is reasonable and harmonizes well with the supervisory superintendence of the Lokpal in the proposed Lokpal Bill, which is now exercised by CVC under Section 8 (1) of the CVC Act. The Committee recommends the above provision, suitably adapted to be applicable in the relationship between the Lokpal and the CBI. [Para 12.44]

72. The next stage of the criminal process would go back to the Lokpal with full powers of prosecution on the basis of the investigation by the CBI. The following points in this respect are noteworthy:

- Clause 15 in Chapter IV of the Lokpal Bill, 2011 already contains adequate provisions in this regard and they can, with some modifications, be retained and applied.

- The Committee’s recommendations create, again for the first time, a fair demarcation between independent investigation and independent

- prosecution by two distinct bodies, which would considerably enhance impartiality, objectivity and the quality of the entire criminal process.

- It creates, for the first time in India, an independent prosecution wing, under the general control and superintendence of the Lokpal, which, hopefully will eventually develop into a premium, independent autonomous Directorate of Public Prosecution with an independent prosecution service (under the Lokpal institution). The Committee also believes that this structure would not in any manner diminish or dilute the cooperative and harmonious interface between the investigation and prosecution processes since the former, though conducted by the CBI, comes under the supervisory jurisdiction of the Lokpal.[Para 12.45]

73. The next stage is that of adjudication and punishment, if any, which shall, as before, be done by a special Judge. The Committee considers that it would be desirable to use the nomenclature of ‘Lokpal Judge’ ( or Lokayukta Judge in respect of States) under the new dispensation. However, this is largely a matter of nomenclature and existing provisions in the Lokpal Bill, 2011 in Chapter IX are adequate, though they need to be applied, with modifications. [Para 12.46]

74. The aforesaid integrates all the stages of a criminal prosecution for an offence of corruption but still leaves open the issue of departmental proceedings in respect of the same accused.[Para 12.47]

75. The Committee agrees that for the Lokpal covered personnel and issues, it would be counter-productive, superfluous and unnecessary to have the CVC to play any role in departmental proceedings. Such a role would be needlessly duplicative and superfluous. For such matters, the Lokpal should be largely empowered to do all those things which the CVC presently does, but with some significant changes, elaborated below.[Para 12.48]

76. Clauses 28 and 29 of the Lokpal Bill are adequate in this regard but the following changes are recommended:

(i) The Lokpal or Lokayukta would be the authority to recommend disciplinary proceedings for all Lokpal or Lokayukta covered persons.

(ii) The CVC would exercise jurisdiction for all non Lokpal covered persons in respect of disciplinary proceedings.